Commons Picture of the Year; Wikidata licensing: Two for the price of one—do the popular Commons image contest and Wikidata licensing serve the community as well as they should?

I could have written the usual, relatively uncritical Signpost coverage of the results of the Commons Picture of the Year competition in "News and notes" or as a "Special report", as we did here, here, and here, for example. But this year feels like the right time to take a look at a fundamental issue concerning the competition.

I should say up-front that I'm neither photographer nor photographic critic; indeed, my last international trip amply showed a talent for turning great photographic opportunities into forgettables. However, I do have a passing acquaintance with the English Wikipedia's featured picture forum from the two years for which I wrote the Signpost's "Featured content" page. There I was first exposed to the expert opinions of our regular reviewers, and it was through reading their comments, as a weekly drop-in observer, that I could at least learn the basic criteria and even a few technical terms (alas, without impact on my flunky tourist photography).

In highlighting featured promotions I also became aware of a fundamental difference between featured pictures and the other featured forums: articles, lists, and topics are solely the work of Wikimedians; in contrast, featured picture candidates are of three types: first, those that have been wholly created by a Wikimedian; second, existing images selected and improved—often very skilfully—by a Wikimedian; and third, existing images merely selected and uploaded without input except for categorisation and a short description note on Commons. Items in these categories involve strikingly different levels of skill and creativity by our people, but if promoted, they're given the same featured status regardless.

I don't mind lumping images of these three types together in a single forum, whether on the English Wikipedia or on Commons, which has its own featured process: there, the throughput and number of active reviewers are just too small to fractionate them into categories. All the same, I must admit to a slight bias in my featured content Signpost coverage towards highlighting the work of Wikimedians over raw uploads from elsewhere. It seemed proper to give more oxygen to creative skill and originality in the community than to great images just grabbed from out there because they happen to be freely licensed.

However, the double-round annual Picture of the Year competition—open to raw uploads of external images, apparently on equal footing—is huge by comparison, and affords much more opportunity to corral those three types of images so that the design and photographic skills of our community can be more fitly recognised. In round 1, 3678 people cast more than 175,000 votes for the 1322 candidates; in round 2, more than 4000 people cast 11,570 votes for 56 finalists (the top 30 overall and the top two in each category). While the competition does aim to encourage uploads to Commons, it seems odd to put all into the same bag, whether the fruits of the highly creative work of community members or merely upload grunt. In any event, this year NASA images won both first and sixth places: I'm sure NASA isn't even aware of these accolades, and probably wouldn't care either way. Are we squandering our social rewards?

Kudos to all place-getters: there's some remarkable work here. However, allow me to bemoan the fact that the second round is not judged by a panel of experts after a democratic vote for the first round. In my view, the second-placed image belies the wealth of artistry in so much Islamic architecture: we're faced with half the image seriously underexposed almost to the point of black, the rest a bath of oversaturated colour without compositional depth. The design of the stained-glass windows does not appear to be worth highlighting—not to me, at least. With apologies to the photographer, I'm disappointed.

To return to the theme of astronomy, the third place-getter, taken from an external site, is indeed striking technically and artistically in several respects, although the gendered and vaguely sexualised title was clearly not thought through ("Milky Way lying above a lady"). At least there's a human in the picture.

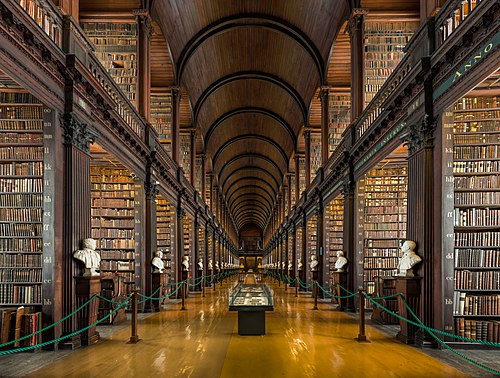

David Illif's photograph of The Long Room at Trinity College Library gained fourth place and exemplifies this Wikimedian's prolific contribution to our repertory of article-ready pictures—and his talent for capturing grand interior perspectives.

Fifth place went to an image of the Seljalandsfoss waterfall in Iceland, by Diego Delso, who will be well-known to Wikimedia's featured-picture communities. His work also won 11th place with an image of a basilica church in Colombia, in which ornate gothic revival protrudes from a richly structured craggy hillside. The seventh and eighth place-getters were taken from Flickr, and No. 12 was released by the British Ministry of Defence.

No. 9 was of a pine-forest in Brazil just after dawn, by Heris Luiz Cordeiro Rocha. Here, light and shape combine to produce a serene, fog-streaked landscape. Tenth was Arild Vågen's picture of Rådhuset metro station in Stockholm, in which symmetry, straight lines, and reflection sit astonishingly within earthen walls and ceiling, challenging our preconceptions of railway stations as industrial forms.

Despite my misgivings about the structure of the competition, it has been a pleasure as usual to view so many entries of technical and artistic beauty. Congratulations to all involved. Tony1

Andreas Kolbe's thought-provoking piece "Whither Wikidata?" sheds light on several troubling trends regarding the usage of Wikidata by third parties. Google and Microsoft, who secured well over half of Wikidata's initial funding, are now enjoying the fruits of our community's hard work with absolutely no strings attached. No considerations of public good.

As Kolbe shows, Wikidata usage by these companies lacks attribution, and this means end-users don't know the provenance of the data they are served up, and the community loses potential new editors. We are also harmed in a third way: any modifications made by others to this rich dataset do not return to the community at large: as far as Google and Bing are concerned, Wikidata is very much there to exploit as "free" as in "free labor".

Copyleft is the only assurance we editors have that our work will not be proprietarized (privatized, in plain English) down the line by third parties, who only truly care about free culture insofar as they can cash in on it, completely ignoring the spirit of sharing that is the cornerstone of our community.

A solution for this problem would be to move to a copyleft license. The Open Database License (ODbL), for instance, was designed for datasets such as Wikidata, and has been used most notably on OpenStreetMap. ODbL's "ShareAlike" provisions (much like those of CC BY-SA) would be a tremendous step forward for our project, as it would ensure that Wikidata and its contributors are credited and that any derivations of this work will be released freely for all.

We should not fear vain threats made by those who wish to use us as mere free labor for their enterprises. Wikidata's mission is not "to be the most used dataset in the industry". Its purpose goes way beyond that: we are translating knowledge into structured knowledge.

We should not bend to the power of industry monopolists. No amount of venture capital or ill-disguised "donations"—really investments made with certain expectations in return—should interfere with our goal of making knowledge accessible. In this context, accessibility means "trickling down" freedoms; every downstream user needs to have the same guarantees we are granting upstream.

Ideally, this should not be a controversial point. Among all Wikimedia projects, Wikidata is conspicuously alone in not being copylefted. Perhaps we should start asking why that is the case and whose interests benefit from weak licensing choices, and start to organize ourselves to fix this. NMaia

Discuss this story

Requiring attribution for Wikidata

Requiring attribution and the same license for derivatives for Wikidata seems like common sense. Is there a good reason we are not doing this? Doc James (talk · contribs · email) 00:22, 16 June 2016 (UTC)[reply]

Of various points Andreas made about Wikidata, I thought the area raised about commercial reuse was the weakest, really. And of the points made above, I think the non-copyright nature of "facts" is the strongest.

Argument by analogy with Wikipedia text is certainly not convincing, nor should it be. Attribution is actually different from referencing, even though both are of interest in the general matter of understanding "provenance", which does indeed matter. I would say the way forward is with WikiCite, i.e. trying to standardise and solidify sourcing from external references. Which is what everything rests on. If you think about the potential of data-mining, e.g. the ContentMine project, the key aspect would seem to be machine-readable referencing styles everywhere.

Legal status is going to be less important than "audit trails" for purported facts. Charles Matthews (talk) 08:19, 17 June 2016 (UTC)[reply]

So re-users of data who don't indicate their sources will lose credibility, no? If their "business model" is simply to claim they have "authoritative" data, without giving adequate referencing, they become like, well what? Tabloid newspapers, that is one thing that comes to mind. Plagiarists, is another.

I think those comparisons show something about the idea of imposing obligations or constraints on users. Frankly, there are shameless people out there anyway, and it is better not to get too involved with them, when one can avoid that. Facts really can be treated differently from authored material. Well, I suppose at some point this is an issue on which people may have to agree to disagree.

How Wikipedia Works conformed to the GFDL by adding many pages of attribution, just to quote WP; neither Phoebe or I (mostly Phoebe) would want to go through that again. If you go seriously into the data reuse question in education, though, you can see why CC0 might be a good idea (allows lightweight reuse in cases of AGF). I wouldn't like to think that fairly generic tables of the world's longest rivers, or time-series of rainfall data in Australia, would have to carry compliance overheads

In any case, we here have plenty of experience of the hazards of using unreferenced material, and very little in the sort of direction you suggest. Looks like Stallmanitis to me. Charles Matthews (talk) 18:24, 17 June 2016 (UTC)[reply]

I don't think you need to call me naive. You are talking about an effect created by a lack of critical thinking (of some people). I'm talking about a chilling effect on reuse, in schools short of resources for example. If what schools taught about the Internet was more up-to-date, critical thinking everywhere would be in a better state. The naivety doesn't lie with those like me who have written on information literacy.

Here's what I mean, in an example, anyway. With a few facts from Wikidata, I can make the multiple-choice question "Was Albert Einstein's birthplace (a) Bremen, (b) Munich, or (c) Ulm?" This sort of thing can and should be done on a large scale, starting from Wikidata. If I created a database of such questions (and this is a project of mine) it would be helpful to record both the authoring of questions (say user-generated and bot-generated), and the source of Wikidata facts (dated, for maintenance purposes).

But if someone just wants to generate a printed quiz with 20 questions, using a front end of such a database, or just by hand from Wikidata, I don't a legal framework to compel them to carry along such provenance metadata is what we want. In practice it would, I believe, have a "chilling effect": any mention of intellectual property does. We should in this case be thinking that such quizzes could, more slowly and "by hand", be taken from Wikipedia pages.

In any case I don't intend to lose sleep over Google's Knowledge Graph. I think prioritising Wikimedia's brand in terms of easy reuse is worth more attention. Charles Matthews (talk) 09:02, 18 June 2016 (UTC)[reply]

Copying my ML post: Added to that, even if it were possible to copyright facts, I think using restrictive license (and make no mistake, any license that requires people to do specific things in exchange for data access is restrictive) makes a lot of trouble for any people using the data. This is especially true for data that is meant for automatic processing - you will have to add code to track licenses for each data unit, figure out how exactly to comply with the license (which would probably require professional help, always expensive), track license-contaminated data throughout the mixed databases, verify all outputs to ensure only properly-licensed data goes out... It presents so much trouble many people would just not bother with it. It would hinder exactly the thing opens source excels at - creating community of people building on each other's work by means of incremental contribution and wide participation. Want to create cool a visualization based on Wikidata? Talk to a lawyer first. Want kickstart your research exploration using Wikidata facts? To the lawyer you go. Want to write an article on, say, gender balance in science over the ages and places, and feature Wikidata facts as an example? Where's that lawyer's email again? You get the picture, I hope. How many people would decide "well, it would be cool but I have no time and resource to figure out all the license issues" and not do the next cool thing they could do? Is it something we really want to happen?

And all that trouble to no benefit to anyone - there's absolutely no threat of Wikidata database being taken over and somehow subverted by "enterprises", whatever that nebulous term means. In fact, if Google example shows us anything, it's that "enterprises" are not very good at it and don't really want it. Would they benefit from the free and open data? Of course they would, as would everybody. The world - including everybody, including "enterprises" - benefited enormously from free and open participatory culture, be it open source software or free data. It is a good thing, not something to be afraid of!

Wikidata data is meant for free use and reuse. Let's not erect artificial barriers to it out of misguided fear to somehow benefit somebody "wrong". Smalyshev (WMF) (talk) 02:46, 23 June 2016 (UTC)[reply]

POTY

As the uploader of the winning image... Eh, screw it. I'm disappointed that won too. It's a fantastic image, and I was excited to find it, but I believe that's the only image I've ever had the slightest connection to to even make it into the final round. I work in image restoration, and, no matter how carefully one restores an image, it's never going to get that much visiblity in any Commons promotions or contests. For example, I'd argue File:Billy Strayhorn, New York, N.Y., between 1946 and 1948 (William P. Gottlieb 08211).jpg is better than a different restoration being sold, and File:Frances Benjamin Johnston, Self-Portrait (as "New Woman"), 1896.jpg is a massive improvement over both the original source and the best copy we formerly had - but the work done is completely invisible at POTY; for all the POTY voting pages indicate, they may as well be images just grabbed from elsewhere because they're free-licensed.

It's disenheartening. Commons offers monthly contests - but they're only open to photographers. POTY tends to value prettiness at thumbnail over any other consideration, meaning we get situations where, for example, an attempt at making the image more artistic means it's misleading and can't be used in an encyclopedia (the image is a composite: it shows an event that can only happen while electricity is flowing, but removed the source of electricity in photoshop to make the picture more interesting).

POTY could handle this; indeed, even if it simply emphasised the winners of the various categories (and accurately categorised them - this year, all sorts of non-paintings were put into a category named "Paintings") - then it would at least make a start on recognising the variety of content.

I think Commons is a wonderful project, but what it most heavily promotes and what it seems to get used for most outside of itself and Wikipedia seem to be very different things. Adam Cuerden (talk) 00:50, 16 June 2016 (UTC)[reply]

I share the concerns of Tony1 about imported images winning the contest. The contest should promote Wikimedia contributors. If Creative Commons hosted such a worldwide contest, that's fine, but we should focus on our community of collaborators. --NaBUru38 (talk) 17:30, 18 June 2016 (UTC)[reply]

I really love the POTY competition but also find it slightly frustrating. I vote in both rounds but am totally unqualified. I'd love for the second round to be judged by an expert panel. Perhaps one instruction could be given (both rounds) that might favor community created/restored images: entries should be judged in part on how educational (I almost wrote 'encyclopedic', but want to include value to all Wikimedia projects) they are. In part to make up for my inability to pick between two stunning images (or even notice obvious flaws) I try to bias my votes in this way. But I 99% just love the POTY competition and think it does an OK job of picking educational-looking winners already. Still I'd love to see tweaks which make it even better, perhaps by partially disenfranchising me. On the other topic, I think CC0 is fine for Wikidata, but I'm slightly vexed to read folks who want a conditional license suggesting the FDL of data rather than CC-BY[-SA]. Mike Linksvayer (talk) 21:39, 19 June 2016 (UTC)[reply]

Tony1, I caution against thinking that "a panel of experts" would do better. I remember reading an aphorism about photo competitions (which concerned those who enter their own images, but I guess the same is true of those who have their own favourites among the entries): "If your image does well, the judges were wise and had a good eye for what makes an outstanding image. If your image does badly, the judges were blind fools." Any popularity contest, fully open to anyone regardless of experience and training (never mind recognised expertise), is going to choose "popular" images. Experts in most creative fields tend to have a different agenda. Think of popular music, popular fashion, art that people actually buy to put on their walls, books that people read in the millions, vs the kind of bands that only music critics love, clothes that only supermodels could wear, art that common people don't understand, books that are worthy but dull, etc, etc.

We had experts judging the final stages of WLM UK in the two years it ran, and I have to say I was very disappointed with their choices. See here and here. There are a few good ones, but compared to what normally passes at Commons FP on a daily basis, I suspect Tony, even with his unexpert eye, would also be disappointed at their choices. Some were very poor technically, and in 2013 many were very low resolution. And generally the winning photographers weren't regular at WP or Commons and didn't stay. Unlike the regulars, they submitted small, heavily-processed and arty images rather than the accurate documentary and high-resolution images that our community values. In other words, the experts didn't share our values.

I don't think Adam's restoration images will tend to do well in any popularity contest. Appreciating the work that went into the restoration (vs the talents of the artist who drew or photographed the original) is too complex a task and not suited to pressing "Like" buttons and when faced with over a thousand excellent alternatives. I agree with him that the two lightbulb winning images in previous years, though great works of art, aren't the finest example of educational images, being contrived and manipulated.

I recommend you consider POTY as just the bit of fun that it is, and accept the attributes of popularity contests, good and bad. Most of the Featured Pictures on Commons are excellent. That's the point. Don't consider the selection of a handful of images out of over a thousand as a contest designed to "recognise" the skills of our community. We have other forums that do that. And don't make the mistake of thinking the result reflects Commons' community values -- the voting is open to anyone with a Wikimedia account and it certainly attracts those from all projects. As I browse the images in the round one of the contest, I can celebrate the fine free works that Commons offers as a repository of educational works. As a creative contributor to Commons (rather than an uploader of others' works) of course I would like to be appreciated, but Commons is more than just an image bank for amateur photography, so POTY should not ignore those who do the uploading or who negotiate free licensing. -- Colin°Talk 12:19, 21 June 2016 (UTC)[reply]

Articles aren't only created by Wikimedians

I just wanted to point out that there is a fundamental error in the second section of this piece. Articles are not at all only the work of Wikimedians — often we use or adapt other CC or PD content, which is the very same thing as what you highlight. I've been involved with the Heart article which to a large degree builds upon the CC-BY textbook CNX: Anatomy & Physiology, which is currently undergoing GA review. I would be devastated if it failed that review only because it uses content produced externally. That goes against the very nature of Wikipedia's mission to spread knowledge. Even when we don't take and adapt text directly we include and adapt free images, and sound-files, and videos, placing them in articles in a way where external content is part of our creations. Wikimedia should be a platform for all free content, and we should simply promote what is best, not what we happened to know is produced by a friend from Wikipedia. Carl Fredrik 💌 📧 15:48, 16 June 2016 (UTC)[reply]

It's a question of the ratio of the external sourcing and internal input of skill and effort. Yes, the balance goes both ways: you'll notice that a little time went into writing the description page for the winner (and significantly more for No. 6, which along with the noise reduction does at least exonerate from my point about outsourcing—though not enough to win a top place, in my view, and I suspect that only a tiny proportion of votes were cast by people who had taken this into account). Let's also consider that the task of choosing and integrating images into an article, and writing appropriate captions, is normally greater than the energy put into writing description pages for externally sourced images.

You write: "Wikimedia should be a platform for all free content, and we should simply promote what is best, not what we happened to know is produced by a friend from Wikipedia." My responses are first that it's nothing to do with friends on Wikipedia, or the whole featured-content system would be discredited by accusations of nepotism. Second, featured picture forums already provide a significant way of judging and rewarding the best free content, internal and external. Third, I didn't propose that POTY be restricted to internally produced material—one improvement might be to retain the current blindness to the internal–external divide in the round 1 category competitions and give those results more publicity, but to restrict the more prominent and symbolic round 2 to internals; and it's probably not the only solution. Tony (talk) 05:03, 17 June 2016 (UTC)[reply]

"Copyleft matters"? Facts should also matter.

I have commented on some important factual issues in this post on a mailing list and maybe it is best to keep replies there. But for the benefit of readers here, let me quote the main points I replied to the author:

Please check the linked thread to see if the author has replied. Maybe one or the other point I make here can still be clarified by the author, who may have sources that I am not aware of. (It would be greatly appreciated if replies posted here could be sent to the mailing list as well, so as to keep the thread complete there.) --Markus Krötzsch 22:54, 16 June 2016 (UTC)[reply]

Why public domain makes sense for Wikidata

As a potential Wikidata contributor, I am driven by the following consideration: I want to contribute to Wikidata, so no one will ever need to repeat my efforts. Were share-alike or attribution stipulations placed on Wikidata, I would not contribute. Share alike creates incompatibilities. For example, share alike would prevent integrating Wikidata with CC BY-NC content. Integration is especially important with respect to data (the most valuable applications occur only once data is integrated). Additionally, data licensing is a relatively new legal issue, with much uncertainty. I support public domain dedication (such as CC0), because it reduces the burden of content reuse. There is a growing consensus in the scientific data fields that any stipulations regarding data reuse are damaging. I've personally experienced how licenses that do not waive all copyright protections make data integration a nightmare. I strongly urge the Wikidata community to consider what option will be the best for the longterm reuse and preservation of Wikidata content. I firmly believe that the future will be built on public domain data rather than data encumbered with incompatibility- and legalese-ridden licensing.

Daniel.himmelstein (talk) 13:25, 20 June 2016 (UTC) Daniel Himmelstein[reply]

Wikidata is a connector

As a contributor to and user of Wikidata, I feel strong about keeping Wikidata under a CCZero waiver. The original op-ed article ends with: "Among all Wikimedia projects, Wikidata is conspicuously alone in not being copylefted." Copylefting (or not) has been heavily and religiously debated for many, many years in the open source community. I have never seen strong examples why either would be better for open source. Second, data is not text and is not source code. It's different and "conspicuously alone" is a false argument that suggests that for data the same arguments apply as to other content types. "Perhaps we should start asking why that is the case" Two possible reasons why this is and should be the case I just discussed. Add to that that in many jurisdictions, facts are not copyrightable in the first place, though in many jurisdictions too, a collection of facts can be (like in The Netherlands). About: "and whose interests benefit from weak licensing choices," that's the wrong way around. CCZero is a stronger license (actually, it's not a license, but a waiver): it gives people more freedom, removes many more hurdles. And exactly these strong freedoms are for me the reason to contribute my effort (time, and with that, money) to Wikidata. Wikidata, with a strong mechanism for sourcing data, and identifiers, can play a criticial role in connecting scientific knowledge. That is greatly inhibited by changing Wikidata to a copylefting license. It would be a significant step back. Finally, I disagree with this point: "and start to organize ourselves to fix this" There is nothing to fix. CCZero without copylefting gives more freedom and for me that main reason to invest my time. Before you start talking about "fixing", realize you will also loose. Egon Willighagen (talk) 12:09, 22 June 2016 (UTC)[reply]

What would it take to do it?