Ashgate Publishing, 191pp, hardcover, ISBN 978-0-7546-7433-7, September 2009

"Everything is radical about Wikipedia except for the actual articles", Dan O'Sullivan told the recent Critical point of view conference in Amsterdam. Many aspects of Wikipedia's community and knowledge production, he said, are profound departures from the Western cultural tradition, and the suppleness, pluralism and interconnectedness that Wikipedia achieves amount to "a change in the very nature of knowledge itself". But in his view, while an article in old-style encyclopedias such as the Britannica can gain authority by adopting a particular angle, Wikipedia’s conventions of neutrality and consensus—the "blended compromise"—are a conservative formula that can weaken the distinctive voice of an article, resulting in a certain sterility.

Dan O’Sullivan is a British historian with his name on five books, most recently this one, which traces what he sees as antecedents of the "wildly successful" Wikipedia phenomenon back more than 2,000 years. The author describes a set of pre-Internet communities of practice (whence the book's slightly clunky subtitle) in terms of their aims, participants, transactional costs, public relations and legacy. But rather than deepening our insights into Wikipedia, these historical vignettes disappoint: most of the connections with the earlier communities of practice are obvious or tenuous, and we are subsequently presented with a decidedly superficial analysis of how Wikipedia is "conservatively radical" in relation to them.

Much more is known about The Royal Society of London, created in 1660 by a group of professional gentlemen to champion the value of evidence-based knowledge. The boldness of setting up the Royal Society could have been underlined if we had been given a sense of the tumultuous state of England at the time; and here, too, was a chance to follow up the concept of the expanding public space, explored in the opening, theoretical chapter but nowhere thereafter. The conclusion that the Society was "without patronage" and neutral on questions of politics sits oddly after an account of the royal patronage, both financial and political.

While the Royal Society anticipated the Enlightenment, the Frenchman Denis Diderot was one of the leading figures of that movement. Having introduced Diderot a little unfairly as a hack writer, jailbird and one-time pornographer, O’Sullivan describes how he took up a proposal by Parisian printers for a French translation of the English Cyclopedia (1728). But the Encyclopédie was no mere translation: it turned into a visionary 28-volume work, with more than 70,000 articles plus illustrations. This is an interesting account of how Diderot and hundreds of collaborators strove not just to assemble knowledge, but to move it firmly out of the hands of an elite and into the public domain. However, tracing a parallel between Wikipedia and the Encyclopédie on the basis of the use of "the latest technology" to produce and disseminate their knowledge is dubious without proper investigation.

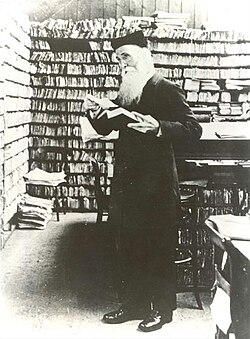

The Scotsman James Murray was the principal editor of what would become The Oxford English Dictionary. Like Diderot a century before, he was the hub of an almost unmanageable flood of contributions from widely dispersed writers, and was plagued by subprofessional standards—an inevitable trade-off in harnessing the huge volunteer workforce that sifted the literature for contexts in which words are used. This might have been the opportunity to explain why so many Wikipedians are keen to give their time and effort gratis and largely unacknowledged. But the reader has to work hard to winkle out what could have been a clearly stated analogy: that the OED project offered a conduit between ordinary people and a high-profile, prestigious publication to which they could make piecemeal contributions without the burden of professional deadlines; and that Wikipedia, too, has redefined expertise, unlocking within editors' personal timeframes their specialised knowledge, even if just on their own locality or school. The picture might have been filled out later in the book by asking whether earning social esteem within the Wikipedia community, in combination with this private–public conduit, might be what fires editors to donate hundreds of millions of dollars worth of their labour.

The subsequent treatment of Wikipedia is wide of the mark, wasting an opportunity to deeply probe its community and process of knowledge production. Instead, some 30 pages are devoted to reproducing versions of a single article at three stages of its development, with insubstantial conclusions. Almost 20 pages are devoted to setting out a cumbersome numerical system for assessing articles and presenting a kind of detached how-to-use-it guide. Yet the basics are missing. There is no recognition of the hierarchy of rules and standards—the pillars, policies and guidelines. The relationship between articles is discussed in terms of the category system, but not of the use of summary style to reach deeply into the nooks and crannies of human knowledge through the creation of "daughter" articles of increasingly narrow scope—the ultimate tree. Only one of the six featured-content processes is mentioned, featured article candidates, and there is no discussion of how it has evolved as an influential model for article quality—the sharp rise in standards over the past few years, the complex relationship among nominators, reviewers, and delegates, and the jostling among the FAC process, the Manual of Style, the main page exposure of featured articles, and the rule that no editor owns any article.

O'Sullivan sees the cauldron of wikipolitics largely in terms of how neutrality is handled. If he contends that Wikipedia's pillar of neutrality enfeebles its voice with a have-a-bet-each-way formula, a comparison would have been useful with the editorial policies of the world's only two non-commercial, independent state broadcasters—the British and Australian Broadcasting Corporations—since they are charged with addressing a similar need to balance the angles of competing interest groups. Still untouched is an analysis of the extent to which neutrality in practice is skewed towards the cultural perceptions of the educated, middle-class anglophones who call the tune at Wikipedia. And there was scope to probe the robustness of the no original research pillar—to ask whether there can ever be a clear distinction between original research and the handling of secondary sources in Wikipedia's articles.

The author stresses the "comparative lack of hierarchy" in the community, quite forgetting that the freedom to edit is subject to constraints for social and legal reasons, and is overseen by Wikipedia's own police force and judiciary. The book might have traced how official power in the community has developed to deal mainly with behavioural issues, even though matters of behaviour and content are often entangled. Related to this could have been an examination of how sovereignty, originally emanating entirely from Jimmy Wales, is evolving in the light of his changing role.

This book needed to penetrate the dynamics of Wikipedia, characterised as they are by the contest of opposite forces. Among these are democracy versus consensus (still poorly defined), reform versus the status quo, privacy versus the management of identity fraud, and the ownership of intellectual property versus fair use. The world's most prominent information site brings into sharp relief many of the issues that will be played out in "real life" societies over the coming century. We await a book that analyses in depth how these dynamics are unfolding on Wikipedia.

Discuss this story

Prologue

Wikipedia is using the latest technology? Not in 2001, not in 2010. Paradoctor (talk) 17:12, 11 May 2010 (UTC)[reply]

The Hidden Order of Wikipedia