Last week the WMF announced the release of its long-awaited open-access policy. In a statement on the Foundation's blog, executive director Lila Tretikov wrote that "Wikimedia is committed to nurturing open knowledge for all, unrestrained by cost barriers ... the Wikimedia movement has a longstanding commitment to open access practices. Today, we are excited to formalize that commitment with this policy."

Open access is a movement among researchers that was initially aimed at making research findings accessible to their colleagues, and now increasingly to the public. It evolved through the 1990s and early 2000s as scholars and scientists discovered the Web as a platform for communicating their findings. It became more formalized when the Budapest Open Access Initiative coined and defined the term. The Initiative sparked several follow-ups, among them the Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and Humanities, which was signed by several Wikimedia entities, including the Foundation.

Daniel Mietchen, an active researcher in data science and member of WikiProject Open Access, told the Signpost that while many researchers welcome open access in principle, the incentive structures in universities and other research institutions do not always make this an easy choice for their own publications. In response, research institutions, funding bodies, governments and other organizations have begun to modify the incentive landscape through open-access mandates. These mandates require that research findings from specific institutions or funded through specific programs be made available open access.

The Wikimedia movement as a whole has a long history of engagement with open access; in particular, the Foundation has been supporting interactions with the research community, be it through the Research Committee (which oversees the monthly Research Newsletter published as part of the Signpost), through support of the WikiSym/ OpenSym annual conference series, or through other forms of significant support. Initial work on an open-access policy was started in 2010, consolidated and presented at Wikimania in 2011, but never formalized into an actual policy; at the same time, open-access policies have continued to expand in reach and scope.

The Foundation has meanwhile continued to take increasingly strong stances on the issue. In 2011, the research committee put together a response to an EU public consultation on the nature of scientific information in the digital age. In 2012, it responded to a similar consultation by the White House. A few months later, the WMF moved to endorse a petition made to the White House by the public-access group Access2Research, asking for “free access over the Internet to journal articles arising from taxpayer-funded research” (Signpost coverage). In 2013, the White House responded with a directive that moves in this direction by requiring the largest public research funders in the US to develop taxpayer access policies similar to the NIH Public Access Policy that has been in effect since 2008. This policy development is still ongoing.

Open-access policies are particularly important in the context of the Wikimedia movement. Not only do members of the Wikimedia movement work to provide "open access to knowledge" for all of our readers—a goal complementary to that of the scholarly open-access movement—they directly benefit from the increasing transparency of journal publications for studying, sourcing and illustrating knowledge available through Wikimedia projects.

Mietchen says that in this context, "the WMF’s open-access policy shows interesting deviations from standard features of its academic siblings:

By establishing its own open-access policy, the Foundation has put its cards on the table and strengthened the alignment of its own research initiatives with the open-access movement. Further details on what the new policy means for researchers interested in the Wikimedia projects are in the open-access policy FAQ.

Since that Wikimania session in 2011, there have been multiple meetings in the movement on open access (while one specifically on the new policy has been proposed for Wikimania 2015) as well as dozens of talks (e.g. here or here) and blog posts (e.g. here or here) on the interaction between Wikimedia and open access (further Signpost coverage is linked in the sidebar).

Providing access to research is not always straightforward, highlighted by the long history of the proposal for an open-access policy for research coordinated with the support of an organization as committed to open access as the WMF. This is illustrated by the annual discussions about the open-access status of the research presented at WikiSym, a conference that spurred important contributions to Wikipedia research (2015, 2014, 2013, and 2012).

The new WMF policy on access to WMF-supported research—with its emphasis on open licensing and the option of publicly justified exceptions—could act as a catalyst for bringing the research and Wikimedia communities closer together. It is likely to lead to greater accessibility to research findings for contributors and other users of Wikimedia platforms. R, T

The Wikimedia Foundation this week announced the on-boarding of Guy Kawasaki to the Board of Trustees. Kawasaki replaces Bishakha Datta, who served from March 2010 to December 2014, in one of the four board seats reserved for "necessary expertise". In his introduction in the Foundation blog Kawasaki stated that "There are few projects in the history of the world that can have the long-term impact of Wikimedia ... the democratization of knowledge that Wikimedia stands for has been a long time in the coming, and I relish applying my passion and experience to this amazing mission." Executive director Lila Tretikov states that "Guy grasps what really moves people. His passion for extraordinary experiences is a perfect fit for Wikipedia’s remarkable mission."

The Board of Trustees is the WMF's "ultimate corporate authority"; as a new trustee, Kawasaki is now one of the ten people tasked with stewardship of the Wikimedia Foundation (and, through it, of the overall movement). Before his appointment to the Board, Kawasaki was chief evangelist for Canva, an online graphic design tool; he has formerly served as an adviser to Motorola and as a chief evangelist at Apple, where he "developed and popularized the concept of 'secular evangelism' for Apple’s brand, culture, and products". He has written ten books on the topics of business technology, marketing, and entrepreneurship, the first of which, The Macintosh Way, was published in 1989, and the most recent, The Art of Social Media: Power Tips for Power Users, late last year. Although the blog post provides little detail about why the Board chose Kawasaki, specifically, it is not hard to see what expertise Kawasaki, an extremely active social-media influencer (see, for instance, his LinkedIn roll or his Twitter), is meant to bring to the board: a recent Forbes story went so far as to call The Art of the Start 2.0, a refresh of a 2004 Kawasaki publication, "The New Entrepreneur's Bible". R

Once when I was young, growing up in the 1990s, my father pulled his collection of railroad slides out from the basement, set up his projector, and shared a glimpse into American railway history with our family. I was too young to remember the slides distinctly, but I do remember being really impressed by the experience. Many years later, a sequence of seemingly unrelated events would lead me back to these slides and a vision for digitizing them. In 2013, while I was the Wikipedian in Residence at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library, I met Edward Vielmetti for a conference panel on the relationship between wikis and libraries. Before the panel, he introduced me to ArborWiki, a LocalWiki for all things related to Ann Arbor, Michigan. Then, while I was attending an ArborWiki meetup in 2014, I met David Erdody, who runs an analog-to-digital media conversion service called A2Digital. After learning that he had the equipment and expertise necessary to digitize slides, I immediately thought back to my father's collection and the possibility of digitizing it.

The slides themselves were taken both by my father (David) and his father (my grandfather, Lawrence). Most were created in the Midwestern United States, especially Michigan, Indiana, and Illinois, chiefly during the 1960s and 1970s (although one photograph of an Ann Arbor Railroad Steam Special dates back to circa 1950). Their featured subjects are largely passenger trains, and due to their dates of creation they document both the last decade of private passenger rail service in the United States and the early years of Amtrak. According to my father, the majority of the photographs were taken by my grandfather, who was an avid amateur photographer; however, both my father and my grandfather would often go railfanning together, making it impossible to discern who took each individual photograph in most cases. For this reason, all of the digitized photographs credit "Lawrence and David Barera" as the photographer. However, because my father is my grandfather's legal heir, he controlled all of the copyrights to the entire collection, including for those photographs taken by his father.

I eventually decided to have the slides digitized as a Father's Day gift for my Dad, after which I agreed to terms with Erdody and handed off all of the slides to him. Initially, I thought about this project as simply a way to make the slides conveniently accessible to my father, and after receiving the digital surrogates from Erdody I began uploading them to Flickr for this purpose in May 2014. While doing this, I realized that there was tremendous potential for the further sharing of these digitized photographs, so I asked my father if he would be willing to release them under a Creative Commons license so I could also upload them to Wikimedia Commons. He graciously agreed to this proposal and released them freely under the CC BY-SA 2.0 license, which is conveniently supported by Flickr.

My father's motivation for freely licensing these images was rooted in the fact that his slides had been underused prior to their digitization; in his own words, they had been "tucked away with other family artifacts" and only ever brought out of storage "every dozen years or so". Further explaining his rationale, he noted that "I was proud of the quality of most of the photos, and thought there was no better way to honor the work of my father than to make his photos available for public use."

In less than a year since they were uploaded, my father's donation of 146 original images (now 151 total files, including retouched derivatives) to Wikimedia Commons has certainly benefited the Wikimedia community, as over 10% have already been added to Wikipedia articles (chiefly but not exclusively on English Wikipedia). Interestingly but not surprisingly, my father's decision to freely license these images has also benefited him directly in the form of both subject identification and color correction, largely thanks to Wikimedians Mackensen and MagentaGreen, respectively. By voluntarily releasing his collection of railroad slides into the commons, my father has benefited from the volunteered efforts of other users while also enriching the content of both Wikimedia Commons and Wikipedia.

In light of my experience with this digitization project, I believe that motivations for freely licensing older analog personal photographs are very similar to those for contemporary digital photographs, including the motivations that catalyzed my own personal photographic contributions to Wikimedia Commons back in the mid to late 2000s. The economics of their creation appear to be essentially the same, necessitating only a camera and the desire and ability to take photographs, often as a hobby; I believe that this makes the amateur analog photographer's decision to freely release his or her images very similar to the equivalent decision made by contemporary amateur digital photographers. The major challenge, however, is the cost and equipment required to digitize these images before they can be uploaded or freely licensed. While the cost is not insignificant, from my experience it is not prohibitive either ($0.50 per slide in my case), which for me at least made it a feasible and affordable gift idea.

From my personal experience I would certainly recommend A2Digital, although according to Erdody it is a "strictly local service"; while he told me that he would be willing to "receive materials by mail from anywhere", he also described the idea of mailing slides or similar analog materials back and forth for digitization as "very risky" (emphasis in the original). As a protective measure, he recommends that his customers deliver their materials to him by hand, which is precisely what I did. While this worked perfectly well for me as an Ann Arbor resident, it simply will not suffice for the rest of the world.

Due to the fragility of the medium in question, successfully digitizing slides nonetheless requires, as Erdody terms it, "a grassroots solution". Asking your local library or historical society about how they digitize slides or negatives is probably the best place to start. Although not terribly common, according to Erdody, some libraries do provide lists of their digitization vendors; an example is the state-run Library of Michigan in Lansing, which maintains this webpage on the subject. Perhaps the easiest way to locate such a service, however, is to simply search the Internet for "slide digitization" and the name of your city, town, or the nearest metropolitan area. However you find a slide digitizer, though, I'd highly recommend that you explore the possibility of digitizing any slides you may have of potential interest to Wikipedia and other Wikimedia projects. In terms of the final results in my case, I think that my father said it best: "I know my Dad would be pleased and proud to know that his work was finally being enjoyed and appreciated by railfans (and others) all over the world."

Four featured articles were promoted this week.

Three featured lists were promoted this week.

Twenty-two featured pictures were promoted this week.

The Wikimedia Commons' annual Picture of the Year contest has concluded, with 6,698 people voting—its largest participation yet. The contest has been held since 2006 and "aims to identify the best freely licensed images from those that during the year have been awarded Featured picture status". The photographers hail from three continents and include prolific Wikimedians as well as non-Wikimedians who didn't even know their photographs were in the contest. We attempted to contact all of them and heard back from six of them. The photographs capture every continent but Australia, and even reach outer space.

First place: Two Julia butterflies (Dryas iulia) drinking the tears of turtles in Ecuador.

This photograph, taken with a Canon EOS 5D Mark II in 2012, was posted on Flickr by the Ministry of Tourism of Ecuador. Butterflies often seek liquid in odd places. The practice of tear drinking in particular is called lachryphagy.

Second place: An emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri) in Antarctica jumping out of the water.

This photograph was taken by Christopher Michel, a member of the famous Explorers Club, in December 2013. It was taken with a Nikon D4 and posted on his Flickr page. He told the Signpost that he took this picture on his fourth trip to Antarctica. He said "I spent hours waiting to capture that penguin shooting out of the water!"

Third place: High above Tocopilla, Chile, a boxcab belonging to the Sociedad Química y Minera de Chile moves downhill to the Reverso switchback.

David Gubler, a prolific photographer of trains, took this photograph with a Canon EOS 5D Mark III in 2013. He told the Signpost it was one of his favorite pictures. It may look like he's standing in a precarious position, but Gubler assured us it wasn't that steep. The difficulty was in finding a vantage point to capture the train and " a nice view of the sea and Tocopilla", while "the scary bit was actually the access road" on the way to the tracks.

Fourth place: Nakhi people carrying the typical baskets of the region in Lijiang, Yunnan, China:

Uwe Aranas took this photograph with a Canon PowerShot G11 in 2012. The Nakhi are an ethnic group who live in the foothills of the Himalayas in Yunnan. The scene is from a performance an amphitheater which uses the natural scenery of Jade Dragon Snow Mountain as a backdrop.

Fifth place: Polar Bear (Ursus maritimus) jumping, in Spitsbergen Island, Svalbard, Norway.

This photograph was taken by wildlife photographer Arturo de Frias Marques with a Nikon D700 in 2011. Polar bears are the iconic symbol and a chief tourist attraction of Spitsbergen.

Sixth place: The Horsehead Nebula (also known as Barnard 33), a dark nebula in the constellation Orion.

This picture was taken by Californian astrophotographer Ken Crawford in 2011. Crawford took this photo using his backyard observatory, including a 20 inch RC Optical Systems Carbon Fiber Truss telescope, in northern California. Crawford told the Signpost that this particular image took twenty hours of exposure time and seven different filters. He believes this image is popular because of the recognizable shape of the nebula and the striking astronomical features. "The glowing pink/red hydrogen provides a beautiful back drop to this amazing region of the deep sky," he said.

Seventh place: The Serra dos Órgãos National Park, with the Dedo de Deus (God's Finger) in the background, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

This photograph was taken by Carlos Perez Couto with a Nikon D90 in 2014. Serra dos Órgãos is a national park founded in 1939. Its most iconic feature is the Dedo de Dues, which resembles a hand with a finger pointing towards the sky. The formation appears on the state flag and coat of arms of Rio de Janeiro .

Eighth place: Head of a Calliphora vicina, face view.

Sam Droege of the USGS Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab took this photograph in 2014. Droege told the Signpost that the mission of the Lab is "providing statistically robust information about the status of plants and animals for little to no cost to the public". While most of the photographs they take are bees as part of their educational and informational mission, they also take pictures of other things to engage the public or "just because they are too beautiful to pass up". This fly was found during a nature event on the National Mall for school children. This photograph is actually a combination of about fifty individual photos combined with a computer program called Zerene Stacker in a process called focus stacking.

Ninth place: A pair of Mandarin ducks (Aix galericulata) at Martin Mere, Lancashire, UK

WWT Martin Mere is a nature reserve near the residence of Francis C. Franklin, who took this photo with an Olympus PEN E-PL5 in 2012. He told the Signpost "I’d noticed the pair on the rocks amongst some other non-mandarin ducks, and given the neutral background I thought I might get a decent shot of them if I waited around for a few minutes. Luckily, the other ducks soon cleared off and then the mandarin pair decided to gaze into each others eyes!"

Tenth place: A cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) silhouetted against a sunset, in the Okavango Delta, Botswana.

Arturo de Frias Marques took this photograph with a Nikon D2X in 2014. The Okavango Delta is one of the Seven Natural Wonders of Africa. The cheetah, one of the many species which make the delta their home, is the fastest known land animal and can reach speeds of up to 120 kph.

Eleventh place: Sunrise in morning mist near Dülmen, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany

Dietmar Rabich told the Signpost he took this photograph on an early Sunday morning, a time he prefers for photography. Rabich said he has to be patient to capture the image that he wants - "Sometimes I'm waiting weeks and months for the right moment". That waiting paid off in 2012 for this photograph, taken with a Canon EOS 600D. The time of day provided just the right light, as well as a lack of traffic that allowed him to capture this moment while standing in a local roadway.

Twelfth place: A C-130T Hercules aircraft with the Blue Angels flying over a platoon of Marines at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, United States

The photograph was taken by Staff Sgt. Oscar L. Olive IV, USMC in 2014 and posted on the official Flickr page of the United States Department of Defense. The Blue Angels are a popular flight demonstration squadron of the United States Navy.

This week's list is reminiscent of lists from the early days of this project: a preponderance of famous faces, Reddit threads, and Google Doodles. Predictably, the arrival of St. Patrick's Day topped the list, while the arrest of Robert Durst proved surprisingly popular. Events of global significance, such as the devastation of Vanuatu, were pushed out this week.

For the full top-25 list, see WP:TOP25. See this section for an explanation of any exclusions. For a list of the most edited articles of the week, see here.

As prepared by Serendipodous, for the week of March 15–21, 2015, the 25 most popular articles on Wikipedia, as determined from the report of the most viewed pages, were:

| Rank | Article | Class | Views | Image | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Saint Patrick's Day | 2,783,603 |  |

Every man has his day, at least if he's a saint. And when your day happens to involve copious alcohol consumption and opportunities for gradeschool cruelty, it is bound to be popular. A Google Doodle doesn't hurt either. | |

| 2 | Robert Durst | 1,508,008 | It's not often that a film documentary has an impact on an actual murder investigation; Errol Morris's 1988 documentary The Thin Blue Line famously led to the exoneration of Randall Dale Adams, and now, the The Jinx: The Life and Deaths of Robert Durst, the new documentary by Andrew Jarecki (Capturing the Friedmans), has provided evidence leading to the re-arrest of Robert Durst, the wealthy son of a real-estate family suspected of, but never convicted for, three murders. It says something about the inner dynamics of the Durst family that his brother greeted the new evidence by saying he was "relieved" and "grateful" and that, "We hope he will finally be held accountable for all he has done." | ||

| 3 | Anna Atkins | 953,069 |  |

The photographic and botanical pioneer (one of, if not the first person to illustrate a book with photographic plates) got a Google Doodle on her 216th birthday on 16 March. | |

| 4 | Alex (parrot) | 941,143 |  |

If his trainer is right, then this African grey parrot, who died unexpectedly in 2007, could very well have been the most intelligent non-human animal in recorded history. Not only did he have a vocabulary of over 100 words, he apparently understood what those words meant and could identify objects by name, even if they were different colours or shapes. But one day, Alex appeared to take things to another level completely. He turned to his trainer and asked, "What colour am I?" the first existential question ever asked by an animal. This was noted in a Reddit thread this week, which quickly filled up with contributions from parrot owners telling tales their own pets' abilities.

Note: in the name of honest journalism I should admit that the above grey parrot is in fact NOT Alex, since his actual photo is copyrighted. Still, he'd pass in a crowd. | |

| 5 | Natalia Kills | 902,335 |  |

That's a rather aggressive stage name, it must be said. Anyway, the British singer apparently lives up to her name (somewhat) because she is currently engulfed in a minor scandal over bullying a contestant while acting as a judge on the New Zealand version of The X Factor. | |

| 6 | To Pimp a Butterfly | Unassessed | 828,825 |  |

The latest album from Kendrick Lamar (pictured) was released on 16 March. |

| 7 | Christian Laettner | 811,567 |  |

How does a man named Christian Laettner respond to a TV documentary called I Hate Christian Laettner? Well if he happens to be the Christian Laettner who polarised fans throughout his college basketball career and stomped on rival team member Aminu Timberlake's chest during his career-defining match in 1992, he takes it in his stride and publicly apologises to his most famous victim, who promptly accepts it. | |

| 8 | 2015 Cricket World Cup | 765,014 |  |

Down from 923K views last week as the tournament played through the quarter finals. With India still in, along with a raft of English-speaking countries (Australia, New Zealand, South Africa), do not expect it to leave this list any time soon. | |

| 9 | Saint Patrick | 740,598 |  |

It is perhaps not surprising that Ireland, the only predominantly Catholic country in the English-speaking world, would produce the English-speaking world's most popular saint. It is, however, somewhat surprising that he has been embraced by pretty much everyone, regardless of religious affiliation. | |

| 10 | Monica Lewinsky | 692,719 |  |

The former White House intern and owner of the dress that almost brought down the free world gave a TED Talk this week on a pertinent subject in which she is well-versed: cyberbullying. |

A monthly overview of recent academic research about Wikipedia and other Wikimedia projects, also published as the Wikimedia Research Newsletter.

This social network analysis[1] looks at the entire corpus of Wikipedia biographies (with data from English, Chinese, Japanese and German Wikipedias). The authors created several thousand networks (unfortunately, this short conference paper does not discuss precisely how) and used the PageRank algorithm to identify key individuals.

The authors attempt to answer the question "Who are the most important people of all times?" Their findings clearly show that different Wikipedias give different prominence to different individuals (the most prominent people, for the four Wikipedias, appear to be George W. Bush, Mao Zedong, Ikuhiko Hata and Adolf Hitler, respectively). The Eastern cultures seem to prioritize warriors and politicians; Western ones include more cultural (including religious) figures. Interesting findings concern globalization: "While the English Wikipedia includes 80% non-English leaders among the top 50, just two non-Chinese made it into the top 50 of the Chinese Wikipedia ... Japanese Wikipedia is slightly more balanced, with almost 40 percent non-Japanese leaders". Findings for the German Wikipedia are not presented. Though the authors don't make that point, it seems that no women appear in the Top 10 lists presented. Overall, this seems like an interesting paper (it also received a writeup in Technology Review), through the brief form (two pages) means that many questions about methodology remain unanswered, and the presentation of findings, and analysis, are very curt. On a side note, one can wonder whether this paper is truly related to anthropology; given that the only time this field is referred to in this work is when the authors mention that they are "replacing anthropological fieldwork with statistical analysis of the treatment given by native speakers of a culture to different subjects in Wikipedia."

See also our earlier coverage of similar studies:

A paper in Advances in Physiology Education[2] claims to assess the suitability of Wikipedia's respiratory articles for medical student learning. Forty Wikipedia articles on respiratory topics were sampled on 27 April 2014. These articles were assessed by three researchers with a modified version of the DISCERN tool. Article references were checked for accuracy and typography. Readability was assessed with the Flesch–Kincaid and Coleman–Liau tools.

The paper found a wide range of accuracy scores using the modified DISCERN tool, from 14.67 for "[Nail] clubbing" to 38.33 for "Tuberculosis". Incorrect, incomplete or inconsistent formatting of references were commonly found, although these were not quantified in the paper. Readability of the articles was typically at a college level. On the basis of these findings, the paper declares Wikipedia's respiratory articles as unsuitable for medical students.

The researcher apparently uses an arbitrary unvalidated modification of the DISCERN tool to assess the accuracy of articles. The nature of this modification is not specified; nor is it available at the journal's website as claimed in the paper.

The DISCERN tool does not assess accuracy; rather, it is designed to assess "information about treatment choices specifically for health consumers". As such, the use of this tool is inappropriate to assess the suitability for medical students.

There is no acknowledgement that Wikipedia is an encyclopedia. Several of the DISCERN tool's questions are unsuitable for an encyclopedia. DISCERN questions such as "Does it describe how each treatment works?" and "Does it describe the risks of each treatment?" would be answered on other Wikipedia pages, not on the disease article's page. The author makes an a priori assumption that the medical textbooks used for comparison are perfect sources. The author does not assess those textbooks with the DISCERN tool.

The paper states: "[t]he number of citations from peer-reviewed journals published in the last 5 yr was only 312 (19%)." However this is far superior to the number of citations in the textbooks listed. The chapter on "Neoplasms of the lung" in Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (18th ed.) contains no citations at all. Seven sources are listed in its "Further readings" section, of which only one is from the last five years.

The claim that the article on "clubbing ... had no references or external links" is incorrect. On 27 April 2014, Wikipedia's article on "Nail clubbing" had ten references.

Several of the articles are at a rudimentary stage, containing limited information and lacking appropriate references. However two articles, "Lung cancer" and "Diffuse panbronchiolitis", were assessed by Wikipedia's editors at the highest standard and awarded "Featured article" status. Five more articles, "Asthma", "Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease", "Pneumonia", "Pneumothorax" and "Tuberculosis", reached "Good article" standard. These articles are exceptionally detailed, accurate, and well-referenced. Azer's paper makes no mention of the high quality of these articles.

The research uses an unvalidated tool for an inappropriate purpose without applying a suitable comparator, and inevitably draws incorrect conclusions.

Wikipedia is an encyclopedia. It is not a medical textbook; nor is it intended to replace medical textbooks. Rather, it should be used as a starting point by medical students. The quality of an individual article should be quickly assessed by the reader, and information can be confirmed in the references provided. Missing information should be sought from other sources, such as textbooks. Students should be encouraged to use Wikipedia alongside medical textbooks to assist their learning.

This recent study[3] is a valuable contribution to the small body of work on academics attitudes towards Wikipedia, and is the largest-scale survey in that field so far, with nearly a 1000 valid responses from the faculty at two Spanish universities. The authors find that Wikipedia is generally held in a positive regard (nearly half of the respondents think it is useful for teaching, while less than 20% disagree; similar numbers use it for general information gathering, though the numbers are split at about 35% on whether they use it for research in their own discipline). Almost 10% of the respondents say they use it frequently for teaching purposes. The numbers of those who discourage students from using it and those who encourage student to consult the site are nearly equal, at about a quarter each. Almost half have no strong feelings on this, and fewer than 15% strongly disagree with students' use of Wikipedia – suggesting that the past few years have witnessed a major shift in universities (less than a decade ago, the stories of professors banning Wikipedia were quite common). Unsurprisingly, the faculty is much less likely to cite Wikipedia, with only about 10% admitting they do so.

Almost 90% of the academics think Wikipedia is easy to use, but only about 15% think editing is easy – with more than 40% disagreeing with that statement. Some 2% of respondents describe themselves as very frequent contributors to the side, and 6% as frequent. More than 40% have no thoughts on Wikipedia's editing and reviewing system, which leads the authors to suggest that "most faculty do not actually know Wikipedia‘s specific editing system very well nor the way the [site's] peer-review process works". Asked about Wikipedia's quality, those who think its articles are reliable outnumber those who disagree by two to one (40% to 20%), with an even higher ratio (more than three to one) agreeing that Wikipedia articles are up to date. The respondents are equally divided, however, on whether the articles are comprehensive or not. The authors thus conclude that the impression that most academics are concerned about Wikipedia's quality is not proven by their data. Nonetheless, the artifacts of Wikipedia early poor reception within academia linger: more than half of the respondents think the use of Wikipedia is frowned on by most academics, even though only 14% say they frown on it themselves.

The study goes beyond presenting simple descriptive statistics, giving us a number of interesting findings based on correlations: strongest correlation for teaching use is related to making edits (r=0.59), followed by opinions that it improves student learning (r=0.47), perception of and use by colleagues (r=0.41), Wikipedia's perceived quality (r=0.4), and its passive use (r=0.3). The researchers find that the use of Wikipedia is higher, and views of the site more favourable, among the STEM fields than in the "soft", social sciences. This also explains the Wikipedia's higher popularity among male instructors (which disappears when controlled for discipline and the corresponding much lower population of women teaching in the STEM fields). Interestingly, the influence of age was not found to be significant: "faculty’s decision to use Wikipedia in learning processes does not follow the usual pattern of other Web 2.0 tools where young people tend to be more frequent users."

Of immediate practical value to the Wikipedia community are the findings on what would help the respondents design educational activities using Wikipedia: 64% would like to see a "catalog presenting best practices", with similar numbers (~50%) pointing to "getting greater institutional recognition", "having colleagues explaining their own experiences", and "receiving specific training".

A conference paper titled "Guiding Students in Collaborative Writing of Wikipedia Articles – How to Get Beyond the Black Box Practice in Information Literacy Instruction"[4] (already briefly mentioned in our October issue) reports on the use of Wikipedia student assignments in a somewhat different environment than the usual American undergraduates: this one instead deals with Finnish secondary school students. The authors use the guided inquiry framework, postulating that "information literacies are best learned by training appropriate information practices in a genuine collaborative process of inquiry", and asking how collaborative Wikipedia writing assignments fit into this approach. The findings tie in with the previous research on this subject: students are more motivated than in traditional writing assignments, develop skills in and understanding of wikis and Wikipedia (including its reliability) and more broadly encyclopedic writing. However, students are less likely to develop skills such as identifying reliable sources without specific additional instructions. The researchers note that "the limitation of encyclopaedic writing is that it is not intended to generate new knowledge but to synthesize knowledge from existing sources (i.e., a type of literature review)"; hence teachers who aim to develop skills in generating new knowledge might consider alternative assignments. The paper stresses the need to tailor the Wikipedia assignment (or any other) to the specific class.

A list of other recent publications that could not be covered in time for this issue – contributions are always welcome for reviewing or summarizing newly published research.

The Wikipedia Library's core mission is to provide Wikipedians with the best possible access to research, to help them write better Wikipedia content. When we started this project, we quickly realized that universities, with their extensive collections and journal subscriptions, offered one of the best opportunities for Wikipedians to access scholarly materials.

This led to the creation of our Wikipedia Visiting Scholar program: a university gives a top Wikipedia editor free and full access to the university library's entire online content—and the Wikipedia editor, who is unpaid and not on campus, then creates and improves Wikipedia articles in a subject area of interest to the institution.

Several universities have stepped up to pilot Wikipedians Visiting Scholars: George Mason University, Montana State University, University of California at Riverside, and Rutgers University. This experiment was a great success, with each institution producing at least a dozen well-researched articles, many of which have undergone community review as Featured or Good articles. In this report, we would like to share some of the great content and outcomes created by this Wikipedia Visiting Scholars program and our partner institutions.

The main goal of the Visiting Scholars program is to equip Wikipedia editors with the highest quality resources, so that they can write the most comprehensive Wikipedia articles alongside the help of expert researchers. Montana State University Visiting Scholar Mike Cline, who focused his writing on the environment and Montana's natural history, described the impact university library access had on his work:

| “ | First, access to these resources helps me write better content, in many cases content that would otherwise not be included in Wikipedia. The journal resources via JSTOR and other sources are invaluable in fleshing out content in articles. Second, having access to these resources allows me to step into various content debates and issues and help other editors resolve them with better sources and more accurate content. An example of that was on William F. Raynolds, my access to more scholarly works helped resolve sourcing issues within that article during the Featured Article Review process. | ” |

Montana State resources have become part of Mike's Wikipedia routine, "for every article I work on".

Wehwalt, Wikipedia Visiting Scholar at George Mason University, used his access to develop an impressive 10 Featured Articles in the area of American history. He writes:

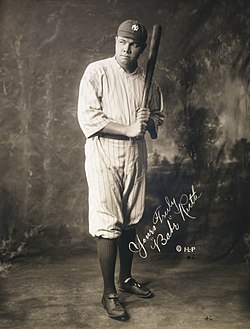

| “ | I'm somewhat envious of the massive academic databases college students have at their disposal these days, given how useful having access to that material is. Since I started at the beginning of April, I've used GMU materials to get six articles to Featured Article status where I did most of the writing: Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, William H. Seward, Babe Ruth, Judah P. Benjamin, John Hay, and Hay's only novel, The Bread-Winners. In addition, there have been collaborations with Designate on John Tyler and Franklin Pierce and others, where works from GMU again came in handy. | ” |

Two other articles that Wehwalt improved, Horace Greeley and Benjamin Tillman, have become featured articles since he first shared his experiences with us! These articles aren't always ones other editors will write about: "Due to his racist views, Tillman is difficult to write about, and not a fun read. But our readers aren't coming just to find information on nice people."

At Rutgers University, we had two visiting scholars, and they saw their work as an opportunity to collaborate with the academic community to help fill diversity gaps on Wikipedia. As Staticshakedown noted, when we asked her about her joint appointment with WeijiBaikeBianji:

| “ | We were both chosen because our goals and interests for the project aligned with the goals of the librarians and graduate students. For this initiative we narrowed the theme into four topics to work on in Wikipedia: Women in Jazz, Newark Jazz history, Asian immigrant experience in New Jersey, and Cultural competence in health care. So far, the collaboration has expanded over twenty-five articles and categories, and created eighteen new articles. | ” |

Library access strengthened the ability for all of our contributors to do what they do best: create content on Wikipedia, content that will become the most-viewed research starting point for hundreds of thousands of readers.

Part of our goal with the Visiting Scholars program is to familiarize Universities Libraries with the practices of Wikipedia and to provide an accessible member of Wikipedia's community on those campuses. Visiting Scholars Chris Troutman and Wehwalt found themselves in conversations with library staff at UC Riverside and George Mason, helping the library or professors become more familiar with Wikipedia’s research and writing practices. Mike Cline learned at Montana State University that there are plenty of opportunities to interact with faculty letting them begin to understand Wikipedia's important role in communicating their knowledge:

| “ | I have also had the opportunity to consult with MSU library staff and faculty when they have desired to create or contribute to Wikipedia articles. In most cases, such faculty and staff have little or no practical knowledge of how Wikipedia really works. I have enjoyed bringing my experience on such issues and notability, reliable sourcing and original research to their attention and helping them devise the best approach in making their contributions to Wikipedia. In several cases, I've helped them by reviewing their work and making appropriate adjustments to drafts in user spaces and in articles themselves. In all cases, the staff and faculty are appreciative of the availability of such consultative services." | ” |

Working closely with the library staff at Montana State helped Mike Cline create an article about the Library's unique trout and salmon archive in addition to a wide range of people and topics written about with a top notch regional collection and the guidance of the experts who curate it. "My only wish, personally, is that they would take even greater advantage of my [consulting] services," Cline said.

Visiting Scholars at Rutgers University also seized further opportunities to participate in the campus environment. Staticshakedown shared:

| “ | This was both Rutgers University's first collaboration with Wikipedians, as well as our first collaboration of this type with an organization. The initiative from Rutgers's side was directed by head librarian Grace Agnew, who has been accessible, friendly, and resourceful throughout the whole exchange. As part of this initiative, twelve members from the Rutgers University team have learned more about how to add content to Wikipedia. Aside from teaching librarians and students about Wikipedia, I have also been the student. Graduate students Yingting and Yu-Hung jointly held a video conference with me on how to access the library resources of Rutgers remotely and how to use Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) to investigate healthcare-related subjects." | ” |

For all of our Visiting Scholars, this has been a great opportunity to fill in major gaps found throughout the encyclopedia and to ensure that the best scholarly materials—not just information that happen to be available on the open web—are leveraged to create public knowledge. This is an important mission, as Wehwalt points out:

| “ | There was a time when Wikipedia was still working to get articles in place on a lot of significant subjects. Well, it has them now, and the number of articles continue to grow. But there’s also a need to improve what we have. Many scholarly articles are hidden behind paywalls for most Wikipedia editors without an academic connection. Visiting Scholar positions are helping us create better content using those sources. Everyone consults Wikipedia, and the need to improve the quality of what we give them through a larger network of experts and scholarly access." | ” |

Wikipedia Visiting Scholars offers an opportunity for the best keepers of knowledge—libraries—and the best sharer of knowledge—Wikipedia—to collaborate in disseminating knowledge to the public. We are proud to be able to facilitate these opportunities and deeply impressed by the contributions of this year’s prolific Visiting Scholars.

Reader comments